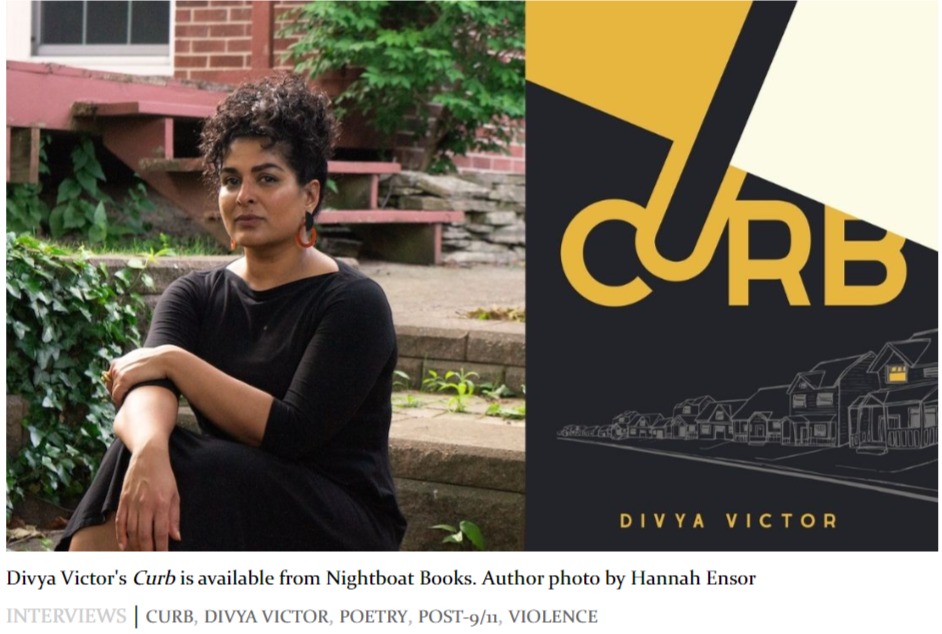

Divya Victor prefaces her new poetry collection, Curb, with four names—Balbir Singh Sodhi, Navroze Mody, Srinivas Kuchibhotla, Sunando Sen. By invoking the names of these four Indian American victims of racist violence in a post-9/11 America, Victor refuses to let their names disappear into mere statistics. In Curb, the South Asian immigrant becomes a subject of study through the speaker’s body (physical and conceptual) as an immigrant in Trump’s America.

While these names only appear again in the context of a few poems, they haunt Victor’s collection with their affect. The collection begins from the individual experience of the speaker and finds itself moving towards the exterior, collective experience.

As Victor explained to me over Google Chat, writing Curb was her way of remaining in the eternal cycle of debt to those she learned from; a debt that can never truly be repaid. This is also her way of creating coalition in the imaginary which, according to Victor, is a much needed coalition of the collective.

—Sanchari Sur

Sanchari Sur

Before Curb existed as a book, it existed as an art exhibit. And that was a few years ago. So, it evolved from artist’s book to poetry collection. Can you speak to that process of evolution?

Divya Victor

In 2017, the printer Aaron Cohick came to me with an idea. I’ve known Aaron since I was an undergrad. We spent a lot of time on stairways, smoking cigarettes and drinking beers and having these big plans for what we could do. And he kind of kept track of them.

He came and said, I want to do a fine press edition through letterpress of something that you would make responding to where you are right now. And it was a really terrifying moment for me because we had just come back to Trump’s America [from Singapore]. And I had just become a mother. And so I was feeling a kind of twinned fear; one on my own behalf, and one on the behalf of my newborn child. And I said to Aaron, I don’t think you’re going to love the content because it’s just going to be very difficult. And he said, I think we should do it. And so, we started having conversations about the form of the book, and the foundation of Curb in many ways was laid in those conversations.

We wanted to make a book that would make the reader extremely alert to the work of reading. I was interested in how humans are read and misread all the time, particularly in public spaces, and how misrecognition is fatal. I was interested in how many cases there were of Indian immigrants, and descendants of immigrants, who are perceived as terrorists. And that was fatal. So, we wanted to make a book that was interested in misreading, difficult reading, effortful reading. And, we wanted to make a book that was very conspicuous and large.

The artist’s book is an accordion fold that has sections that open up vertically as well as horizontally. When you open it up, it can take up an entire dining table. These vertical sections open up like massive maps, because I was thinking very much about the post-1965 move to the United States that many South Asian Americans undertook, and how they would have to engage in map-reading all the time to find their way around everyday places. Reading maps in public spaces is one of the most pronounced ways before the digital era where you would announce your place as a stranger. It’s this conspicuous act of reading that then allows others to read you in that public spot. The book started enacting some of that conspicuousness and effort in navigating public space. So, [the art project] started as that.

While I was doing witness work around violence, I was also always living in a shadow space where I could be safer, where I could be protected, where I was known, where I could not be misread

Read the rest @ https://aaww.org/coalition-in-the-imaginary-a-conversation-with-divya-victor/