Keerthik Sasidharan is a writer whose work has appeared in The Hindu, The Caravan and other publications. He is the author of The Dharma Forest (2019). He lives in New York.

Edited by Sam Haselby

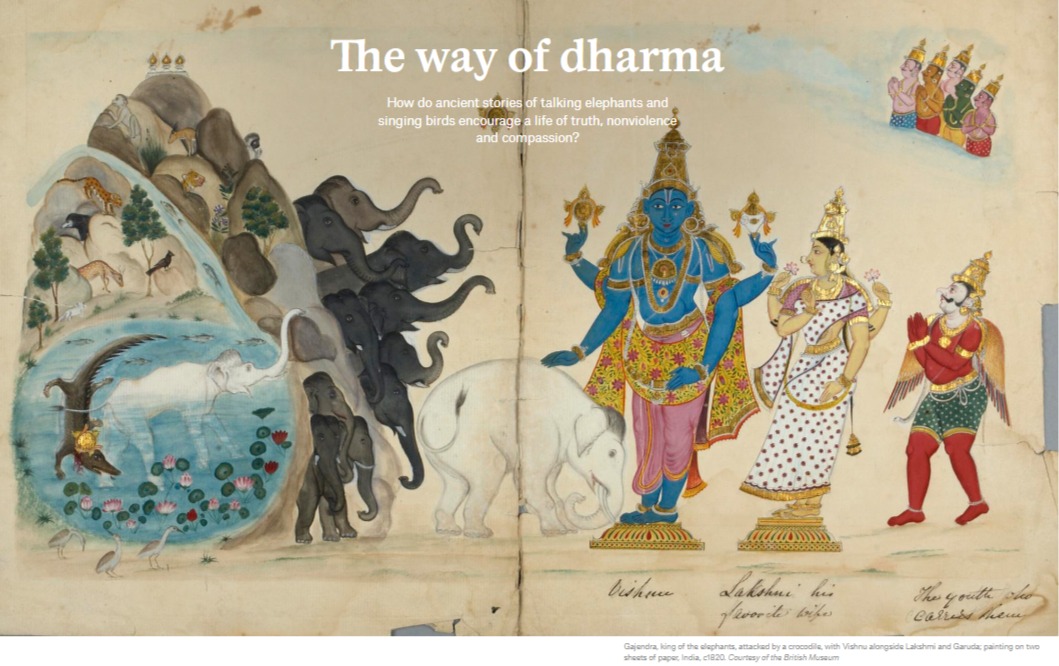

As a child, for every summer vacation, my parents took me to Kerala in southern India to spend three months with my aunt in her large family-estate. It was an age before televisions were widely available and therefore at night-time she told us stories from the vast oeuvre of Indian mythologies called the ‘puranas’. These stories often involved a moral exemplar as a protagonist – a hero who embodied Immanuel Kant’s ‘categorical imperative’ – whose life’s arc exemplified devotion, truth, sacrifice, love and other ennobling ideas. The dramatic twists in these stories came from the gods and their caprice, which tested the commitments of righteous men and women in the face of opportunities to abandon their ideals and save themselves. They invariably never did, at great cost to themselves. My aunt referred to these men and women as ‘symbols of dharma’ (dharma prateekam), although she left that capacious word – dharma – unexplained. Thus, over the years, I learnt stories about Harishchandra the truthful king, Gajendra the worshipful elephant, and others – all of whom were, to my young mind, moral paragons.

For generations, these puranic stories have acted as templates for emulation – learning morality by mimesis – that aimed to break down the natural instincts of selfishness and self-preservation and, instead, rebuild a listener’s inner world in the service of dharma.

The locus of virtue in those stories lay not in ritual or rank but in sustaining commitment to an ideal that demanded some form of sacrifice. When faced with morally complex situations in their own lives – be they a child listening to his aunt, or an audience hearing them from a religious teacher – the listeners could theoretically ask themselves: ‘What would Shravana the filial son do?’ Or: ‘What would Savitri the faithful wife do?’

As a young boy, Mahatma Gandhi had seen a play about the legendary truthful king Harishchandra – a man who sacrifices everything, including his child and wife for the sake of truth-telling. He later wrote about the impact of that story in his life: ‘It haunted me and I must have acted Harishchandra to myself times without number … The thought of it all often made me weep.’

But beyond such instances of moral emulation, at the heart of this pedagogic agenda was also a model of how humans are born: they emerge in a new womb carrying along with them all the deeds and knowledge from their previous lives (the Katha Upanishad from 700-500 BCE summarises this principle as: yatha karma yatha shrutam). The role of these stories is therefore more than just simple moralising: by emulating the actions they prescribe, the stories help cleanse the mind, like a previously used but unwashed utensil, and help improve our abilities to choose better in life. However, nothing is preordained in this pedagogic nudge. Implicit in this model of human birth, or more accurately the emergence of sentient beings, are two outcomes: one can very well ignore these stories and ideals of self-improvement and go on to accumulate more ‘karmic’ muck, or one can live as per these stories and steadily avoid ‘karmic’ burdens. The freedom to choose is yours. Amid all this, there remains a supervening question often left unanswered: what is this dharma that these stories speak of and point towards?

As a child, for every summer vacation, my parents took me to Kerala in southern India to spend three months with my aunt in her large family-estate. It was an age before televisions were widely available and therefore at night-time she told us stories from the vast oeuvre of Indian mythologies called the ‘puranas’. These stories often involved a moral exemplar as a protagonist – a hero who embodied Immanuel Kant’s ‘categorical imperative’ – whose life’s arc exemplified devotion, truth, sacrifice, love and other ennobling ideas. The dramatic twists in these stories came from the gods and their caprice, which tested the commitments of righteous men and women in the face of opportunities to abandon their ideals and save themselves. They invariably never did, at great cost to themselves. My aunt referred to these men and women as ‘symbols of dharma’ (dharma prateekam), although she left that capacious word – dharma – unexplained. Thus, over the years, I learnt stories about Harishchandra the truthful king, Gajendra the worshipful elephant, and others – all of whom were, to my young mind, moral paragons.

For generations, these puranic stories have acted as templates for emulation – learning morality by mimesis – that aimed to break down the natural instincts of selfishness and self-preservation and, instead, rebuild a listener’s inner world in the service of dharma.

The locus of virtue in those stories lay not in ritual or rank but in sustaining commitment to an ideal that demanded some form of sacrifice. When faced with morally complex situations in their own lives – be they a child listening to his aunt, or an audience hearing them from a religious teacher – the listeners could theoretically ask themselves: ‘What would Shravana the filial son do?’ Or: ‘What would Savitri the faithful wife do?’

As a young boy, Mahatma Gandhi had seen a play about the legendary truthful king Harishchandra – a man who sacrifices everything, including his child and wife for the sake of truth-telling. He later wrote about the impact of that story in his life: ‘It haunted me and I must have acted Harishchandra to myself times without number … The thought of it all often made me weep.’

But beyond such instances of moral emulation, at the heart of this pedagogic agenda was also a model of how humans are born: they emerge in a new womb carrying along with them all the deeds and knowledge from their previous lives (the Katha Upanishad from 700-500 BCE summarises this principle as: yatha karma yatha shrutam). The role of these stories is therefore more than just simple moralising: by emulating the actions they prescribe, the stories help cleanse the mind, like a previously used but unwashed utensil, and help improve our abilities to choose better in life. However, nothing is preordained in this pedagogic nudge. Implicit in this model of human birth, or more accurately the emergence of sentient beings, are two outcomes: one can very well ignore these stories and ideals of self-improvement and go on to accumulate more ‘karmic’ muck, or one can live as per these stories and steadily avoid ‘karmic’ burdens. The freedom to choose is yours. Amid all this, there remains a supervening question often left unanswered: what is this dharma that these stories speak of and point towards?

The answer is not easy to arrive at. Even the Mahabharata, that ocean-sized epic tale, reminds us that ‘the essence of dharma is hidden in a cave!’ Vishnu Sukhtankar, the first editor of The Critical Edition of The Mahabharata (1944), writes: ‘I am not going to make the attempt to give you another perfect definition of Dharma, a task which … has taxed better brains than mine.’ But this kind of self-aware humility has not prevented scholars or lay people from forming opinions. A traditional answer has been to look for the etymological origins of ‘dharma’. The root in the Sanskrit language is dhr-, meaning ‘to hold’ or ‘to support’ or ‘to maintain’, and which appears for the first time in the Rigveda – a vast corpus of religious poetry that was arranged in its hymnal form some time during 1400 BCE to 1000 BCE. In Book 8, we find one of its earliest meanings:

Him [the God Indra], the double lofty, whose lofty power holds fast the two world-halves,

the mountains and plains, the waters and sun, through his bullishness.

But the word ‘dharma’, and the derived cognates, is a shapeshifter over time, and occasionally even within one text alone. Stephanie Jamison, the co-translator of the monumental Oxford University Press Rigveda (2014), memorably writes elsewhere that, while the word ‘porridge’ has a specific association to Goldilocks in most of our minds, the word ‘oatmeal’ doesn’t carry that same cultural reference. Thus, while a form like dhárman appears ‘63 times’ in the Rigveda and is relatively staid at that stage in the term’s reception history (‘far more “oatmeal” than “porridge”’, as Joel Brereton put it in 2004), this hasn’t helped modern translators, thanks to at least three millennia of meanings that have smuggled into the term since those verses were first composed.

Dharma insists that the virtues of the child burnish the life of an imperfect parent.

A more immediate and vexing question is how to understand dharma when opposing but equal truths force us into an ethical cul-de-sac. If economic growth results in poverty reduction but also in environmental degradation, whose dharma must one privilege?

Read the rest @ https://aeon.co/essays/how-ancient-dharma-stories-encourage-a-life-of-compassion